I've come to realize that my dissertation could just as easily be about travel as it is about gardens. After all, the gardens I'm studying are spread throughout England and were created over 300 years ago. One had to get to them somehow and in our age of easy travel, we can't truly know what an undertaking it was to venture even 20 miles back then. I was contemplating this fact when Knightly came to mind. You know, the hero of Jane Austen's Emma:

*sniff* Makes me cry every time! I mean, he rode through the rain! To us, spoiled as we are by cars, motorbikes, and busses zipping around on macadam*, that means nothing. So he rode through the rain. Big deal! He got a little wet; so what? So what!? Oh, my dear, I despair of you! Permit me to recall another Austen character, Edward, who, upon returning to Barton Cottage to profess his undying love for Eleanor and, with understandable awkwardness at the beginning of their meeting, satisfies the youngest sister's inquiries by informing them that "the roads were very dry". Travel, my dear, was a very big deal back then!

All these Austen shenanigans happened a hundred years after my heroine traveled around England, logging 1,045 miles in 1697, of which she 'did not go above a hundred in the Coach', meaning she rode a horse. Sidesaddle. Imagine! The state of the roads was major news, no doubt much talked of at all the inns and health spas, and the state of them was appalling, if you must know. Even by the time Edward and Knightly were riding to their fates, roads were perilous. Only city streets were paved with cobbles (well, some cities), and the country roads were sometimes 'pitched' with stones dug up from an obliging field*. Most were dirt tracks seldom maintained, so if you were traveling by coach on a road in an area known for heavy clay soil, in the rain, say, the coach wheels would leave deep ruts that dried into hard ridges, making the roads even worse. In a time when mineral and coal mining were major industries, it wasn't uncommon to encounter an uncovered pit in the road which could swallow your horse (and you with it). And if you lived in a marshy area, roads could be rendered non-existent in a heavy rain or flood. Often times you had to hire a local guide if you were travelling abroad (which in the early 1700's could be defined as anywhere outside a 5 mile radius from your home) because the roads were so bad - or so hard to find - that you could end up hopelessly lost. Or hopelessly dead. Which is why you should be greatly impressed that Knightly rode through the rain.

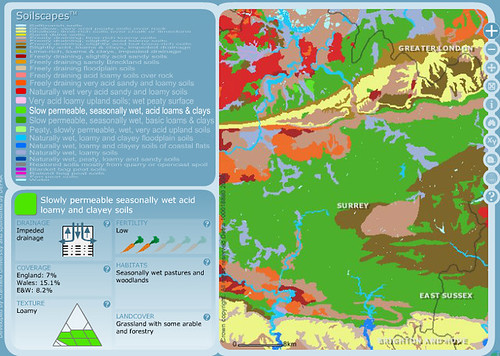

Look, I'll show you:

This is a soil map of Surrey, where most of the action in Emma takes place (yes, I'm a geek, now pay attention). Notice that the predominant soil texture is 'loamy' and the profile indicates 'slow permeable, seasonably wet, acid loams and clays'. Good stuff for the garden, to be sure, not so good for the roads because, as the chart shows, drainage is bad. I think it's safe to say that in Jane Austen's day, when it rained, the roads in Surrey either flooded or became a muddy mess. Rivulets could create small canyons in the road if it wasn't well pitched, and if it flooded enough the stones could have been lifted right off the road leaving a gaping hole masked by muddy water which is what happened to my heroine Celia Fiennes as she travelled the roads in Cornwall:

Knightly could have lamed his horse*! Or met with highwaymen - ohmygosh, I haven't even mentioned highwaymen! It wasn't just a matter of trotting through a spring shower and getting his cravat a little damp, he could have met with major mishap and perilous threats to life and limb! By riding so recklessly to his beloved, he was risking his life for the mere hope of a chance to win her. This is serious stuff! Oh, that a man would ride through the rain for me!

"Here Indeed I met with...more lanes and a deeper clay road, which by the raine the night before had made it very dirty and full of water; in many places in the road there are many holes and sloughs where ever there is clay ground, and when by raines they are filled with water its difficult to shun Danger; here my horse was quite down in one of these holes full of water but by the good hand of God's Providence which has allwayes been with me ever a present help in tyme of need, for giving him a good strap he flounc'd up againe, tho' he had gotten quite down his head and all, yet did retrieve his feete and gott cleer off the place with me on his back."

Knightly could have lamed his horse*! Or met with highwaymen - ohmygosh, I haven't even mentioned highwaymen! It wasn't just a matter of trotting through a spring shower and getting his cravat a little damp, he could have met with major mishap and perilous threats to life and limb! By riding so recklessly to his beloved, he was risking his life for the mere hope of a chance to win her. This is serious stuff! Oh, that a man would ride through the rain for me!

Kind of puts a whole new spin on the story, doesn't it? History is so cool that way; it doesn't just tell you how things were then, it throws new light on what you're interested in now. And it makes me rather grateful that the only real issue I have upon commencing my garden tour this spring is deciding whether to go by car or train.

But I have to ask: if you came to a fork in the road*, would you take it?

*mac·ad·am: /məˈkadəm/

| Noun: |

|

*Yogi Berra said it first.