Living in So Cal I tended to encounter two types of people: beach people and mountain people. You'd think, given my proximity to the ocean and the fact that I learned how to swim before I learned how to walk, that I would be a beach person. I wasn't. Nor was I a mountain person. Thus I was forced to dither about in a sort of no-man's land. Having now lived on the East Coast for the past few years, I finally discovered a new category in which to place myself: I'm a stream person. Stream people are not to be confused with river rats - rivers are too large and moody for my taste. Take the Brandywine River, which overflowed its banks and flooded Route 1 in the last big storm. Because of that, I was forced to sit in traffic for over an hour, finally abandoning my intended destination in order to take the long way home, which meant another 45 minutes on the road. All that to go 5 miles, and all because the river had to go and throw a hissy and cover the street, which put me in a bad mood as well.

Streams are much more my speed - they meander and talk to you in a pleasant splashy gurgle, wandering through leafy glades or tranquil woodlands, never seeming to be in a hurry unless they decide to scamper playfully for a bit before again assuming their leisurely pace. And you can usually find the occasional water fowl or forest critter frolicking in a pool or basking in the sun bank side, perusing the latest issue of Forest Weekly. Rivers are good for those with power boats or jet skis, streams are calming and, with the amount of coursework being piled on us, I'll take calm any way I can get it! This is why one of my all time favorite places to relax and enjoy a good meal is on the patio at a local tavern. This is what I get to look at while I eat:

And so it happened that today's ecological learning expedition (fancy talk for 'field trip') turned out to be quite enjoyable for me because it was focused on a stream. The

Stroud Water Research Center in Avondale, PA was founded 40 years ago by a woman named Ruth Patrick. Ms. Patrick was a scientist with the Academy of Natural Sciences and found herself being asked about the health of local waterways, which she was unable to ascertain because she had never seen a 'healthy' stream. She urged her friends, Joan and Dick Stroud, to establish a lab dedicated to freshwater research on their farm in Chester County. Since the White Clay Creek flows through the property, it made perfect sense to the Strouds, and the Stroud Water Research Center was born.

Now covering over 1000 acres, the center studies how manipulating the land affects water quality. With over 40 years' worth of data on the White Clay Creek, I'd say they've gotten pretty good at what they do. They study how water quality and stream life is affected by forestation, reforestation, meadowland, urban development and so on and offered a perfectly logical explanation for why the Brandywine jumped its banks during that storm but the White Clay didn't. You see, when rain falls on a forest the water is slowed by the leaves and spread out over a larger area. It also flows along the branches and down the trunks to the ground where it has a better chance of soaking into the soil, allowing thirsty roots to slurp it up. This means less run off goes charging into the creek which means less chance of flooding. What water does make its way to the stream does so by percolating through the soil which slows it down quite a bit so the stream isn't overwhelmed. The water level will rise somewhat, but flooding doesn't happen with each and every storm. Compare that to the scenario at the Brandywine where the flood occurred: instead of hitting tree canopies the rain hit rooftops. And instead of being channeled down tree trunks to the ground, it was directed down storm drains to the parking lot. No wonder the river threw a hissy fit!

For those who are fans of our natural watersheds but live in a developed area, take heart. Even you can help prevent wanton water run-off by simply installing a rain barrel to capture rain water. Better yet, plant a rain garden that will help slow water sluicing off your driveway or parking lot. Many municipalities - particularly on the west coast, like this

neighborhood in Sun Valley - have begun implementing water management strategies that include rain gardens, infiltration pits, permeable paving, etc. to keep water in the ground instead of allowing it to run willy-nilly into the storm drains.

I also learned that a natural stream meanders. No one knows why water meanders but it does. Even if you pour a stream of water across a smooth surface it won't run in a straight line. There are also different geographies in a stream - there are pools, which are typically deep and still; riffles, where the water moves faster over rocks and gravel; and runs, where the water moves more quickly in a shallower bed without rocks. Given my classmates' uncanny ability to shoot off one-liners and the fact that a few of us are suffering from head colds, I was surprised at the lack of jokes about having a case of the riffles.

Ahem.

Turns out, these features of a stream are more than cosmetic. The riffles serve to oxygenate the water. The runs and pools offer habitats and food sources for all the stream dwellers. Here's another tidbit about natural streams - the leaves from the canopy overhead are what form the basis of the food chain. Whodathunk? This is why, when the state of PA proposed legislation to plant 100 foot buffers of riparian forest along stream banks, native floodplain species such as red maple, river birch, and sycamore became the trees of choice. The leaves fall into the water and provide a food source for the invertebrates which are in turn food sources for the vertebrates, and the merry food chain perpetuates itself. You didn't think fish and ducks all subsist on pellets and breadcrumbs tossed at them by small children and pensioners, did you? Other benefits that trees provide to a natural stream system are the habitats and food stores.

Sometimes a tree dies and falls over, or just plain falls over. At Stroud, the tree is left to decay along the bank or, in the case of the Sycamore above that fell then sent up lateral shoots, is allowed to lay across the stream creating an instant bridge for the resident critters (which really cuts down on commuting when you're a squirrel out acorn shopping) not to mention the fact that certain insects only lay their eggs on the undersides of fallen logs. No fallen logs, no place to lay eggs. No eggs to hatch, no insects. No insects, no food chain. No food chain, no critters. No critters, and your stream is dead, Jim!

Some of the research done at Stroud includes measuring carbon transport through the ecosystem. To do this, material is taken from upstream and collected in tanks where it's allowed to settle for 3-5 days, being gently shaken and stirred to prevent flocculation. The resultant particles, called sestons, are collected. It takes about one cubic meter of stream material to get half a gallon of seston. The particles are mixed with a saline solution and poured into these 30 meter long flumes.

There are four flumes in all, with two covered in bio film to keep the light out. Those two are also treated with a bleach solution so keep them from getting too icky. Rocks and gravel are placed in the flumes to mimic the stream bed and the particles' travel is measured. Similar studies have used fluorescent beads or seed pods from Lycopodium (a type of club moss).

Another study taking place in the greenhouse looks at the effects of phosphorus in the water. In other words, what the stuff that comes out of your washing machine does to your local water system. You're all familiar with TSP - I used to use it to scrub the walls before painting. Turns out trisodium phosphate is one of the chief culprits (along with other eco-unfriendly chemicals) contributing to the algae blooms we keep hearing so much about . The flumes in the greenhouse each contain different levels of phosphorus and, as such, differing levels of algae growth.

The stringy green algae isn't to be confused with the furry brown algae called diatom. Diatom is good. Stringy green gunk is bad. So if you are fortunate enough to own a stream or pond or man-made water feature and notice the rocks and bottom covered in a velvety brown, you are to rejoice knowing that all your microscopic invertebrate friends will never go hungry because Diatom is their most important food source!

Doesn't that make you happy!?

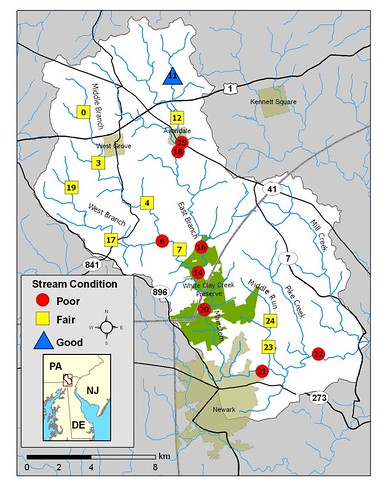

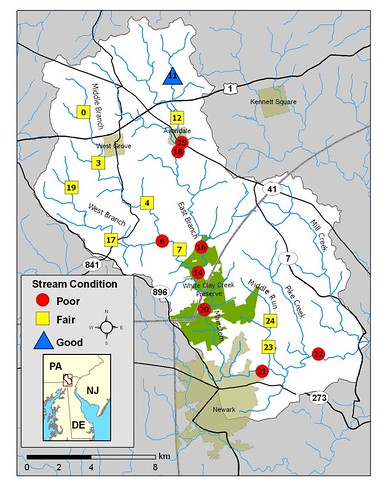

Along with all kinds of highly scientific stuff that's way over my head, Stroud also monitors the stream's water quality. For the last 18 years Stroud has partnered with The White Clay Watershed Association's (WCWA) Stream Watch Program to collect macroinvertebrates (those little guys you can't see without a super-duper microscope but which are the best indication of how healthy - or not - your stream is) and take readings on water chemistry. The map below shows the water quality in several spots along the creek system.

This field trip was not only educational, it was very enjoyable. Where else do you get the chance to learn about such an amazing natural ecological system by actually following the stream on its meandering path? Now when I'm enjoying my lunch on the tavern's patio I'll be able to gaze down into the stream and identify the riffles and runs, will be able to tell with a somewhat educated guess what's causing the stringy green gunk to grow and how to prevent it, and will have a whole new appreciation for the fervor of microscopic life being carried on in so seemingly serene a setting. I don't know about you, but sitting next to a stream contemplating life has just taken on a whole new meaning!