There have been settlements at the site of Fulham Palace since the Iron Age and evidence of Roman occupation has been found nearby. There has been a palace here since, oh, 704 AD, and it was the residence of the Bishop of London until 1973. Bishops were pretty high up in the social, political, and religious echelons so it wasn't unusual for a Bishop to have several houses with a tally of 177 homes for 21 bishops in the 16th century.

Each successive bishop who lived at Fulham left his mark of improvement on the house and gardens, now a listed historical site by English Heritage. Elizabeth I was sent gifts of grapes from Fulham Palace's famous gardens, and one botanically enterprising bishop in the 17th century received rare species of plants from one of his American missionaries, himself a trained botanist. Among the exotics collected at Fulham Palace was a magnolia tree, the first to be grown in Europe.

In the late 1700s a two-acre walled kitchen garden was enclosed when the grounds were remodelled. The current entrance to the walled garden is through a Tudor gateway (and boy, were people short then or what?). There was a vinery, a knot garden was laid out in the 19th century, and fruit trees, espaliers, and loads of herbs and veg grown in the traditional four-quarter garden. Flowers for the house were also grown along the path borders and in the glasshouses.

|

| The restored 19th century knot garden and glasshouses |

Fast forward a few hundred years to the 20th century when the palace had fallen into a state of decay and neglect. The area surrounding the palace, including a medieval moat, was designated a Scheduled Ancient Monument in 1976 and it took the next 30 years for committees to come to agreement on the restoration. A grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund enabled restoration of the building in 2006 and a subsequent grant in 2010 allowed for restoration of the gardens and grounds.

Included in this work was the excavation of the ancient moat, originally over a mile in length, that surrounded the site. The moat will filled in back in the 1920s and loads of builders' debris was chucked in. Only one section of the moat has been uncovered and restored, including the moat bridge, so far but there are hopes to eventually excavate the entire circuit.

|

| A section of the ancient moat and moat bridge, uncovered and restored |

The actual digging took place in two trenches - logically referred to as Trench A and Trench B. Each area measured 25m square, and was divided in to a 5m grid. The top soil was removed by machine and the layers beneath excavated by hoe and trowel. Changes in the soil color and composition indicate the presence of features - planting holes, post holes, tree boles, etc - so these were excavated and recorded before uncovering the following layer.

The work was slow, tedious, and painful (lots of protesting from knees and back) but also really, really interesting. Volunteers cheerily asked with astonishing regularity, "Find anything interesting?" and when we did, a little thrill went through the camp. Maybe one of us would find some Roman hoard or the base of an old fountain. Given that the area had been a kitchen garden, and fields before that, we knew we weren't going to find any lost civilisation but one of the archaeologists had been involved in the discovery of the 18th c. pebble mosaic orangery floor at Chiswick, so you just never know.

In the end, we found lots of potsherds, bits of broken china, and my new obsession, clay pipes and stems. All these things help to date the feature so all the finds are collected in bags and tagged with numbers matching the feature being excavated. The oldest finds at this dig included some Roman pottery, so that's exciting. One feature that I excavated had some pieces of wood rotting in it but we knew the wood was modern because it had been painted. My theory was that it was a tree stake but who really knows?

|

| One of my features - two different fills are present, as are two pieces of wood (barely visible on the far left of the profile), possibly tree stakes? |

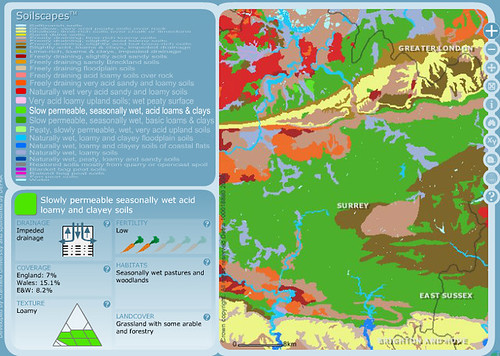

Some features were small and shallow, some were really huge and astonishingly deep. The soil here is sandy and very free draining so clay was mixed in with the fill to help retain moisture for whatever plant went into the hole. The differences in soil composition was pretty clear once you knew what to look for (and gave me flashbacks to soil science class). Fill soil (that which is different than the surrounding soil that was dug into, which is called the 'cut') is saved for analysis and they hope to find some seeds that might indicate what was planted here. This will help them further narrow down the date of the feature as well as help create a planting plan from that era so the gardeners know what was planted here and how well it thrived.

In the end, the dig went back about 250 years to the "post medieval layer" which can be roughly translated to early 1700s. To dig deeper would have required more time and a lot more money than the budget allowed but it would be really interesting to see what, if anything, was to be found at the Roman layer.

Three archaeologists were on site during the dig, and all of them were wonderfully patient with us volunteers. The other volunteers, likewise, were a very able and willing bunch with several going to the dig every day or several times a week. The dig was a great way to get the community involved in the project, was a fantastic hands-on tool for teaching school kids about history, and it attracted so many interesting people - a professor in ancient Greek history, an English tutor, a horticulturist, an archaeology student, a garden historian (!), and so many others with such fascinating backgrounds. All were so enthusiastic about the dig that on the last day when we met for drinks down at the pub at the end of the day, we were all equally sad to see it end. I propose a volunteer reunion in a year's time to see how the rest of the garden restoration is getting on. Of course, most of the volunteers are local so they can visit any time, but I'll have to wait a year or more before I'm able to get back.

|

| Site leader Ian ponders the next move for volunteers and the very long planting features they're investigating |

After learning how to look for features, clean the surface, excavate, record (by drawing and photographing), taking levels and applying what I know of garden history to what was found at the site, I'm convinced that garden archaeology has a very important place in the field of historic garden study. Not only does it give a more complete picture of what occupied the site in previous centuries, but it completes the picture that paper documentation (if there is any) leaves unfinished. While it would be fantastic to jump in a Tardis and see the actual garden as it was 250 years ago, I think the thrill of discovery that archaeology brings would be lost.

So what's next now that the dig is finished? The trenches are being filled back in as I type, and all the written records and drawings will be compiled into a computer generated (CAD) plan of the site. All the scientific data is compiled and a written report is done, then the whole bundle handed over to the people in charge. Based on the final outcome, a new plan of the garden will be designed based on historic information from the dig. The whole process will take another couple of years but the gardeners hope to have the first bit of the garden redesigned and replanted in the very near future, adding a new layer to the history of this ancient site.

|

| Waiting for the sun to go behind a cloud to get a better picture of the trench |

|

| Excavating and discovering, or, men will be boys (I don't think they ever out grow this kind of thing!) |

|

| Indiana Jones had to deal with snakes, we had to deal with foxes |

|

| Bishop Fisher looks on approvingly |

|

| Bishop dahlias blooming in the walled garden |

Fulham Palace is located in Fulham, SW London. The nearest tube station is Putney Bridge and a pleasant 10 minute walk along the Thames Path will take you directly to the palace. The grounds are open free of charge from dawn till dusk. The walled garden and palace have different opening times so check the palace website for details. There is also a very nice cafe open daily from 9 to 5.

*A special thanks to Eleanor Sier, Fulham's Learning Officer, for organizing the volunteers and keeping us well fortified with tea and biscuits, and for making the dig such an enjoyable experience!

*A special thanks to Eleanor Sier, Fulham's Learning Officer, for organizing the volunteers and keeping us well fortified with tea and biscuits, and for making the dig such an enjoyable experience!