It's Tornado Season here in the Mid-South and a series of murderous storms has recently battered Oklahoma. Thanks to the modern marvel that is social media, home videos and photos of the deadly tornadoes allow you to witness the calamity and share in the misery of those affected from the safety of your own mobile device. We've become a society so reliant on recording events via cell phone that I fear we'll lose our ability to observe and relay information any other way. Why worry about being able to describe something when you can hold out your phone and show a picture?

Now imagine if you could read an eyewitness account of, say, the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D. written with perfect clarity 25 years after the event? Well, you can, and that should really blow your mind (no pun intended). If you studied the classics you may have heard the names Pliny the Elder and Pliny the Younger. The elder Pliny was an author, naturalist, and natural philosopher. In his spare time he was also the naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire and personal friend of the emperor Vespasian. He died on that volcanic day, leading his ships on a rescue mission to save the people on the coast from the disaster. Many of them survived, he did not.

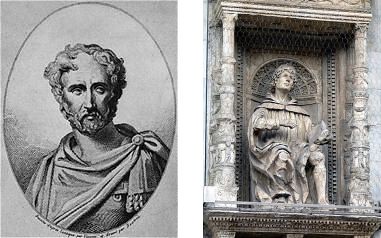

|

| L: Pliny the Elder R: Pliny the Younger (wiki) |

Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, the younger Pliny, followed his uncle into the service of the Roman court. He was a lawyer, magistrate and author, raised and educated by his uncle who no doubt taught him the art of observation in his natural studies. He was staying at his Uncle's house on the northern tip of the Bay of Naples when the mountain exploded. He was 18 years old. Imagine the impression such a spectacle would make. In a letter to the historian Tacitus, penned some 25 years later, he describes the early stages of the eruption:

"My uncle was stationed at Misenum, in active command of the fleet. On 24 August, in the early afternoon, my mother drew his attention to a cloud of unusual size and appearance. He had been out in the sun, had taken a cold bath, and lunched while lying down, and was then working at his books. He called for his shoes and climbed up to a place which would give him the best view of the phenomenon. It was not clear at that distance from which mountain the cloud was rising (it was afterwards known to be Vesuvius); its general appearance can best be expressed as being like an umbrella pine, for it rose to a great height on a sort of trunk and then split off into branches, I imagine because it was thrust upwards by the first blast and then left unsupported as the pressure subsided, or else it was borne down by its own weight so that it spread out and gradually dispersed. In places it looked white, elsewhere blotched and dirty, according to the amount of soil and ashes it carried with it."

Notice he described the ash plume as being "like an umbrella pine, for it rose to a great height on a sort of trunk and then split off into branches". It's this description that is the reason for the umbrella pine in the herb garden at the Getty Villa. The Villa is impressive not only for being an art museum housing Getty's vast collection of ancient Greek and Roman antiquities, it's also an architecturally accurate replica of a 1st century Roman villa, with gardens composed of historically accurate plants, right down to the herb garden.

|

| The umbrella shaped canopy of Pinus pinea (2013) |

|

| The Getty Villa herb garden, with the Umbrella Pine, also called Stone Pine, at the far end. (2013) |

The herb garden was created to resemble a working garden as it would have been 2,000 years ago. While the climate in So Cal allows for genus from all over the world to thrive, Getty chose only historically accurate plants that would have been found in a Roman garden. Not only were these plants useful for food or medicine, many of them had sacred associations cherished by the people of that ancient culture. Here's a run down of just a few that I saw growing at the Getty Villa:

The Stone Pine, apart from being the basis of Pliny's description of the volcanic eruption that so dramatically destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum, is the source of pine nuts, and was considered by the ancient Greeks to be the property of the sea god Poseidon since they grow on the sea shore and the lumber was used for ship building. At the Getty Villa you can pretend you're a very rich Roman, because if you were a Roman of the Pliny's standing, and you had a seaside villa, you would have had an Umbrella Pine in your garden.

The date palm (Phoenix dactylifera), with their distinctive feather duster shape, is where dates come from, which can also be made into date wine. The dry leaves were used to weave baskets (beware the sharp spines on the petiole) and the trunks were hewn to make fishing boats. The genus name derives from the Greek word for the date palm used by Theophrastus and Pliny the Elder, φοῖνιξ (phoinix) or φοίνικος (phoinikos). It most likely referred to the Phoenicians; Phoenix, the son of Amyntor and Cleobule in Homer's Iliad; or the phoenix, the sacred bird of Ancient Egypt. The species name comes from the Ancient Greek dáktulos "date" and the stem of the Greek verb ferō "I bear".

Grapes thrive in the Mediterranean and were an important food source. Conveniently, the fruit was and is ideal for making - you guessed it - wine. Those Romans did love their wine.

At the Getty Villa the grape arbor is made using ancient techniques such as wrapping the structure with new vines which then grow to become a living rope holding the posts and beams together.

|

| Detail of the grape arbor with vines purposefully wrapped around the posts and beams. (2013) |

What's that? You see metal bolts? Well, sure you do. It's the 21st century and there are liability issues with having a structure that people walk beneath in a public garden. But think about this: the Romans invented arches which enabled them to build all those impressive aqueducts, they invented concrete, they even invented the steam engine. They certainly knew how to manipulate precious metals into exquisite jewelry and lesser metals into swords, armor, and deadly accessories on chariots so who's to say they didn't also make metal bolts? Food for thought...

The Romans used herbs for medicine, scent, cooking, even in myth and magic. Lavender attracted bees which made delicious and healing honey. The busy little bees were also useful for pollinating the garden flowers, including the citrus trees, which were introduced to the Med by Alexander the Great.

Bay laurel (Laurus nobilis) was planted around homes and temples, believed to ward off lightning. Laurel wreaths were a symbol of elevated status in ancient Greece and the Romans adopted and adapted this symbolism so that it became a symbol of victory. Crowns of laurel, both real and fashioned of gold, adorned the heads of emperors, conquering generals, poets and the learned upon receiving their degrees. In fact, the French word baccalauréat comes from the Latin bacca, a berry, and laureus, of the bay laurel. The leaves are used in cooking, either fresh or dried, and make a fine seasoning for soups, stews, and pasta dishes. The phrase 'to rest on one's laurels', meaning to be satisfied with past successes, comes from the ancient tradition of being awarded the laurel crown.

In addition to a crown of laurel victorious gladiators were also given olive oil, an extremely valuable and highly prized commodity. Pressed from the edible fruit of olive trees (Olea europea), the versatile oil was used for cooking, cleaning, heating and lighting lamps.

The quince, Cydonia oblonga, native to rocky slopes and woodland margins in South-west Asia, Turkey and Iran, which were under Roman rule in the 1st century, produced an edible fruit (not to be confused with its relative, Chaenomeles, the flowering Quince) that was associated with the goddess Aphrodite. Our friend Pliny the Elder mentioned an edible variety and brides were said to nibble a quince fruit to sweeten their kiss and improve fertility. The furry leaves of lamb's ear (Stachys byzantina) was used for bandages and, if you're in a pinch, makes a very soft natural toilet paper (or so I've read).

Plants and flowers were important to Roman culture and featured prominently in their architecture and decor. The leafy motif on Corinthian columns was first used by the Greeks but was adopted into Roman architecture and mentioned by Vitruvius (born c. 80–70 BC, died after c. 15 BC) in his Ten Books on Architecture. Flowers grown in the gardens were represented in the frescoes that decorated villa walls.

|

| Portrait of the Roman poet Ovid (43 BC - 17/18 AD) wearing his crown of Laurel, by Luca Signorelli (1475-1523). |

Bay laurel (Laurus nobilis) was planted around homes and temples, believed to ward off lightning. Laurel wreaths were a symbol of elevated status in ancient Greece and the Romans adopted and adapted this symbolism so that it became a symbol of victory. Crowns of laurel, both real and fashioned of gold, adorned the heads of emperors, conquering generals, poets and the learned upon receiving their degrees. In fact, the French word baccalauréat comes from the Latin bacca, a berry, and laureus, of the bay laurel. The leaves are used in cooking, either fresh or dried, and make a fine seasoning for soups, stews, and pasta dishes. The phrase 'to rest on one's laurels', meaning to be satisfied with past successes, comes from the ancient tradition of being awarded the laurel crown.

In addition to a crown of laurel victorious gladiators were also given olive oil, an extremely valuable and highly prized commodity. Pressed from the edible fruit of olive trees (Olea europea), the versatile oil was used for cooking, cleaning, heating and lighting lamps.

The quince, Cydonia oblonga, native to rocky slopes and woodland margins in South-west Asia, Turkey and Iran, which were under Roman rule in the 1st century, produced an edible fruit (not to be confused with its relative, Chaenomeles, the flowering Quince) that was associated with the goddess Aphrodite. Our friend Pliny the Elder mentioned an edible variety and brides were said to nibble a quince fruit to sweeten their kiss and improve fertility. The furry leaves of lamb's ear (Stachys byzantina) was used for bandages and, if you're in a pinch, makes a very soft natural toilet paper (or so I've read).

|

| Acanthus leaves and the flowers of species tulips adorn this column at the Getty Villa (2013). |

Plants and flowers were important to Roman culture and featured prominently in their architecture and decor. The leafy motif on Corinthian columns was first used by the Greeks but was adopted into Roman architecture and mentioned by Vitruvius (born c. 80–70 BC, died after c. 15 BC) in his Ten Books on Architecture. Flowers grown in the gardens were represented in the frescoes that decorated villa walls.

|

| Red anemones and white species tulips growing in the Peristyle Garden are included in the frescoes decorating the peristyle walls (2013; click to embiggen). |

These give just a taste of the kinds of plants, their uses and associations in Roman times. For a comprehensive list of the plants found in the Getty gardens, visit the Getty Villa website. Nature was undoubtedly a familiar entity to the Romans, and was well observed as is evident in ancient writing (take the Song of Songs, for example).

It would be interesting to travel into the future and see how many of the eyewitness accounts of our modern disasters survive, and the information they contain. Would they just be images and some media text full of facts and figures, or will someone write it down some years later, recalling details and using elements of nature to describe them? As I was reviewing my photos for this article, I couldn't help noticing that the twisted trunks of these plum trees looked like tornadoes, rising from the ground in a tortured spiral to a spreading canopy floating above.

For information on visiting the Getty Villa, visit their website. For more on the design and use of Roman gardens, see gardenvisit.com. And if you live in the Mid-South USA, heed the warnings and be careful when those storms hit!

No comments:

Post a Comment