Of Uppark, Celia says:

"...I went to Chichester through a very ffine Parke of the Lord Tankervailes [Ford, 3rd Lord Grey of Wark, Viscount Glendale and Earl of Tankerville, 1655-1701], stately woods and shady tall trees at Least 2 mile, in ye Middle stands his house wch is new built, square, 9 windows in ye ffront and seven in the sides. Brickwork wth free stone coynes and windows, itts in the Midst of fine gardens, Gravell and Grass walks and bowling green, wth breast walls Divideing each from other, and so discovers the whole to view. Att ye Entrance a Large Coart wth Iron gates open wch Leads to a less, ascending some stepps, ffree stone in a round, thence up More Stepps to a terrass, so to the house; it looks very neate and all orchards and yards convenient."

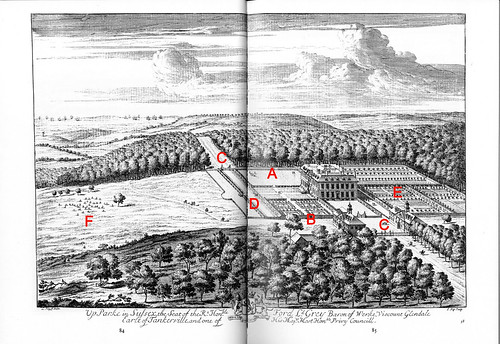

The new house was actually a rebuild of the old house circa 1690 and the fine gardens probably looked a lot like this:

Since Celia never intended her travel diary to be published she was rather, shall we say, free with her style of writing to say nothing of her varying spelling. In case you're not up to 17th century English, much less 17th century English written in a sort of personal short hand, allow me to attempt a translation with the aid of the above image marked for clarification.

|

| (A) bowling green, (B) breast walls, (C) entrance gates, (D) terraces, (E) gardens and orchards (F) deer park |

As you can see, the house stood - and still stands - proudly on the rise of a hill, hence its name "Up Parke" (and yes, before you ask, there was also once a "Down Parke". I find this very common among English place names - they many times have an opposite: Upper Sloughter, Lower Sloughter, Great Dixter, Little Dixter, Broadbottom, Narrowbottom, Right Wingnut, Left Wingnut, etc. If you don't believe me, just have a look at a UK road atlas and try not to let the names make you chuckle out loud).

If you count the windows in the image above you will see that it does indeed have 9 windows across the front (facing left in the image, which is south) and 7 on the side (facing you, which is east). The stone 'coynes' or what in architectural terms is called 'quoins', from the French 'coin' meaning corner, refers to the projecting brickwork or stone on the corners of buildings but the larger stones used on the corners at Uppark are also used around the windows (see photos).

The bit about the entrance is a little tricky. I have it on good authority (well, a volunteer house guide that I spoke to) that the original front door to the house was on the south. There are gates (C) from the road on the west side of the middle terrace in front of the house but entering from that way looks like it would make turning the coach and getting to the stables on the east side a bit tricky as there are no corresponding exit gates on the east side. There are also two sets of gates and two courtyards on the east near the service buildings with two wee riders on horseback to communicate the purpose of that area. The handy Uppark guidebook (new edition first published in 1995) also states that the "approach was from the east via two courtyards" and "the day-to-day entrance was then on the east side of the house", and they ought to know. Right?

I'm finding this to be one of the tricky questions in garden history: 'Where did the carriages arrive?' In the 1800's the entrance to the house was moved to the north, so it's not inconceivable that the approach could have been moved once before, say, from the south to the east. Looking at the entrances on the south and east as they are today, the south stairs and door case are far more grand than the east side, and first impressions being so important, wouldn't you want visitors to come in through the best door? I sure would, and if I had a house like this you can bet I'd want them to come in the front and be impressed!

But then if one were to arrive from the east, would one's coach, and the horses before it, be required to drive all the way around the house to experience the grand south entrance, or would they just come in the side door and see the better doorway when they were shown round the garden (the visitors, not the horses)? Celia's description seems to imply that one entered the house by ascending steps and crossing terraces but without a comprehensive architectural history of the house, who really knows?

I get hung up on the question of where the carriages arrive. I mean, I lose sleep over these things (as evidenced by the fact that I'm typing this at 3am, thanks in part to the drunken brawl that took place outside my window an hour ago). A painting of the house and grounds, the mammoth original of which hangs in the house and covers an entire wall, shows a different view. The house guide in that room told me the painting dates from 1697, which is about when Leonard Knyff was drawing his famous birds-eye view and I doubt the garden could have changed that quickly, unless by some alien force (hey, if they can be credited for stone and crop circles, why not gardens?), but the caption under the image of the painting in the guidebook gives a date of 'before 1734' while the National Trust Collections website lists it at 1720. Agh!

|

| A View of Uppark, c. 1730 or 1720 or 1697 (depending on who you believe) by Peter Tillemans (1684-1734) |

The earlier Knyff and Kip engraving hangs in what used to be the bathroom, and the house guide there had never heard of 'Biff and Nip' so I think we can toss the guide's assertions about the date of the painting right out the window, leaving us with a decade or so to quibble over. Whatever the date of the painting is, it's after the Knyff and Kip drawing published in 1707 because the compartmentalized 17th century gardens have been replaced with Brownian (as in Capability Brown, doyen of the English Landscape Movement) 'natural' gardens complete with pond. The terraces have been smoothed and the two sets of iron gates near the service buildings taken down and probably melted into door hinges. In this image, it's clear that the entrance would be from the east but the ghost of the terraces can be seen in the color of the grass in the painting, and the tell-tale signs of them are still evident in the topography today. Based on Celia's account of her journey, she was on her way to Chichester from Nursted, and very likely would have approached Uppark from the west road which makes her descriptions of the south terraces as the entrance front entirely plausible. So there.

As you can imagine, the garden now looks nothing like what Celia saw, or even what the Tillemans painting depicts, and on the day my friend and I visited it was raining cats. Not to be deterred, we saw the garden and met with the head gardener, Andy Lewis, who said he was actually happy to get out of the office and into the garden even in such bad weather. Sign of a true gardener, that.

|

| New north entrance to Uppark, by Humphry Repton c. 1810 |

What I can tell you, without a shadow of a doubt, is that the house and gardens are now approached from the north, a change made by landscape designer Humphry Repton in the early 19th century. An avenue of Norway Maple (Acer platanoides) under planted with hornbeam (Carpinus) guides the way from the ticket kiosk and we were entertained to see a rogue red-leaf Acer specimen in the otherwise green allée.

|

| North entrance with Repton's classically styled addition c. 1811-14 |

The simple Georgian square house was added to around 1750 and again around 1811 so now you enter the door above and pass through a narrow hallway to the staircase hall, which felt rather odd compared to the grand entrance halls in other houses of this period that I've visited (no photography was permitted in the house so you'll have to take my word for it).

When Andy came to Uppark just a short time ago, he inherited a much overgrown garden suffering from about 25 years of neglect. One formula gives the calculation of three years to recover from every one year of neglect, making it a 75 year occupation to take the garden back to its 1810 form. In order to achieve this, Andy has had to take some drastic measures which not everyone has agreed with. This yew hedge, for example, was given a drastic regenerative cut and the area of ground revealed created an opportunity to plant a new border.

The irregular beds in the lawn were added sometime in the 20th century and are not historically accurate so there is talk of eventually removing them. Not surprisingly this has met with resistance, mostly from the garden volunteers who helped plant the beds in the first place. I understand a gardener's possessiveness but I also understand the historian's desire for authenticity as well as the need to keep plants healthy. Given that garden plants have a sell-by date and don't last forever without some kind of human intervention, be it pruning or replanting, I think working to restore the garden to its 19th century character is a good call even if a few beds have to be sacrificed and some hard cuts have to be made.

These shrubs, branches of which have propagated themselves by layering (rooting into the soil where they touched the ground), have to be taken back in stages. So while fighting what Andy calls "the creep" takes an iron will and stout saw, it has to be done with sensitivity and sound judgement. Just whacking back to the original shrub line or removing self-sown plants would leave gaping holes and make the border look moth-eaten. They may not look great now, but the cut ends of these shrubs will sprout new growth and green up in a year, and in a few years' time, perhaps, more rejuvenation can take place. 'Instant gratification' isn't an option when you're talking about garden restoration.

The house commands a breathtaking view of the South Downs and on a clear sunny day you can see right down to the coast. We tried to imagine it as we sheltered from the incessant rain under the entrance to the old dairy and my friend and I both wore out the Jane Austen quote, "There's some blue sky! Let us chase it!" during our trip. The old bowling green is now a wide meadow grazed by sheep and flanked on either side by the house and managed woodland, creating a fantastic frame for the view beyond. The sheep are pulled off the meadow a few weeks before the garden opens for the season to allow their "added goodness" (i.e. fertilizer) to work itself into the ground before the process is aided by visitors' feet.

The restoration of the gardens follows on the heels of the restoration of the house after a devastating fire in 1989. Ignited by the flame of a blowtorch when the roof was being replaced, the whole house was nearly gutted. After the smoke cleared, the walls were found to be remarkably in tact and the heroic efforts of the fire brigade meant nearly all the contents were rescued (except for the family's personal possessions, all of which were lost in the blaze). All the historic collections - paintings, furniture, tapestries, curtains, china, even large strips of wallpaper - going back to the 17th century were saved. After much debate it was decided that restoration would be a better choice financially than a payout for a complete loss and less than two months later the decision was made to restore Uppark to its appearance the day before the fire. If it weren't for the guides' explanations and the photos in each room of the destruction after the fire, it would be difficult to tell that the place had once been so badly damaged. The plaster or wood carving in some rooms has been left unpainted to show the difference between old and new but the craftsmanship on the new is so good that were it not for the unpainted portions, an amateur (like me) could scarcely tell the difference. One door case in the servants' rooms downstairs has a bit of the charred wood exposed to show the extent of the fire's reach and an exhibit in the basement used burned timbers, lengths of balustrade, plaster, and twisted metal to create a sculpture to commemorate the disaster. I even bought a piece of painted Uppark plaster for £1, which goes toward a maintenance fund for the house.

It's really interesting to follow in the footsteps of a traveller more than 300 years later, to see what she saw, what hadn't yet existed, and to learn how it's being cared for. Being able to compare a landscape with Celia's descriptions and historic drawings like Knyff's gives me the chance to time travel, in a way, and I can't help but wonder what the place will look like in 2312 after Andy's thoughtful stewardship? In one respect it's almost too difficult to think in those terms, but the people who built these estates were doing just that. They had a family legacy at stake, after all. The legacy we leave is no less important, even if our heirs are the general public and not privileged kin.

|

| Celia and me on the south porch at Uppark |

Uppark House and Garden

(The National Trust)

South Harting, Petersfield

West Sussex, GU31 5QR

Telephone: 01730 825857

For opening times and admission, see the National Trust Website:

http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/uppark/

*I'd just like to add that we undertook this garden tour during the wettest week of the wettest April in 100 years, which means we saw more of the insides of houses than we might have had the sun been shining, but that didn't make the trip any less interesting since Celia describes the interiors of some country houses in great detail.

No comments:

Post a Comment