After several weeks of keeping my nose in books and wrestling with computer drawing programs, I decided it was time for a break. Spring is here and I wanted a garden fix. The weather forecast looked favorable, so I decided to venture into Surrey and see Ham House. The fact that it's a well-preserved seventeenth century courtier's house with a restored period garden, which is pretty close to what my travelling heroine Celia Fiennes would have encountered in her many visits to stately homes, is mere coincidence. Even a holiday from the books can be instructive as well as enjoyable.

Being without a car, I took to public transport. Richmond, once a distant country village, is now a suburb of London and easily reached by train. Of course I tried to imagine what the countryside would have looked like 300 years ago and it's not that difficult to mentally sweep away the blocks of council flats and Victorian chimney pots to envision green pasture and woodland. And instead of arriving by train or coach, most visitors would have taken the river which was a much more common mode of transport, the Thames being the M1 of its day.

Location, location, location!

Ham House was built in 1610 by Sir Thomas Vavasour, a knight in Elizabeth I's then James I's court, and he was no fool when it came to deciding where to build a house. Situated smack on the banks of the Thames, it was within easy reach of the string of royal palaces then gracing the river, which afforded a good view whenever the royal barge happened to sail past. Plus, his job as Knight Marshal (basically, Court Police) required him to be on call at all times within a 12-mile radius of London. The location of Ham House meant that he could easily commute to work at court, at whichever palace it was the King's pleasure to hold it.

Sir Thomas died in 1620 and in 1626 Ham became the home of William Murray, 1st Earl of Dysart, who as a boy attended school with the future king Charles I. William's unfortunate lot in life was to be the prince's 'whipping boy'. Whenever little Charlie got into mischief it was William who took the punishment because, well, because they couldn't very well spank the future king, could they?

As adults the two remained good friends and, as a result, William had access to the King's favorites in the way of architects, painters, builders, etc. and it showed in the extravagance that he lavished on his home. Gleaming white marble, dazzling gilded accents, exquisite furniture, polished wood, colorful tapestries, and exotic carpets, cabinets, and curiosities meant that when fellow courtiers stepped through the front doors, they knew they were entering the abode of a man who could boast Major Royal Connections.

After years of Civil War Charles I unfortunately lost his head - literally - in 1649. For the next decade England was ruled by Oliver Cromwell and his puritan dominated Parliament until the people grew bored with that and restored the monarchy in 1660. Charles's son, Charles II, was now king and all was right with the courtly world. Well, almost. But that's a tale for another post.

The tale we're interested in is of Elizabeth, eldest daughter of William Murray, who inherited the house and titles when he died. She married Sir Lionel Tollemache, 3rd Baronet of Helmingham around 1648.

During the Interregnum, Elizabeth was said to be really good friends (like, really, really good *cough*) with Oliver Cromwell, which proved a convenient cover given her Royalist tendencies. Apparently Oliver never suspected a thing, even when she joined a secret organization called The Sealed Knot (I smell a book title) and visited Charles II in Europe.

In 1672 Elizabeth married for the second time. Her new husband was John Maitland, 2nd Earl and 1st Duke of Lauderdale, who had effectively ruled Scotland as Charles's Secretary of State for that kilted country. It was around this time that Elizabeth and her husband used their court connections to have the house at Ham enlarged by enclosing the garden front.

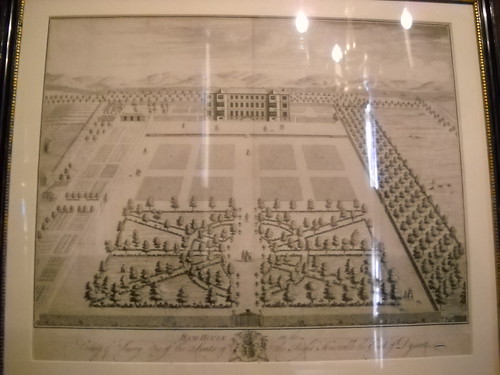

Though the house was beginning to lean toward the Baroque in its new decorations, the garden that it fronted was a celebration of geometry in the formal fashion with 'parterres, flower gardens, orangeries, fountains, aviaries', and statues. Starting almost 40 years ago, the gardens were restored to their former French glory: a central block of grass bisected by comfortably wide gravel paths into four 'platts' with a statue at the center of each, beyond which lies a 'wilderness' of trees and hedges with intersecting straight paths and, through each section thus created, winding serpentine paths. Within these compartments were blooming drifts of daffodils, primrose and snake's head fritillaries. Outside of this was the true wildness of the countryside beyond. All this leafy splendour is to be admired from the raised viewing terrace of the house. Like so:

Now these squares of grass may not look like much to our modern eyes, but back in the seventeenth century they were a major status symbol. Without the convenience of power mowers, these lawns had to be scythed by hand. They were also rolled and swept. It would have taken three gardeners 1.5 days to do all the lawns, which is now done by one gardener in 1.5 hours. It wasn't everyone who had the financial means to employ the number of hands required to keep a garden like this so pristinely manicured.

This part of the garden is enclosed by a high brick wall on the east and west, which hold espaliers of apple and pear on one side, cherry and plum on the other.

The statues of Mercury and Fortuna guarding the entrance to the wilderness are not original, but such statues would have been found here. Though made of lead, squirrels have developed a foot fetish and are nibbling Fortuna's toes off. Ouch.

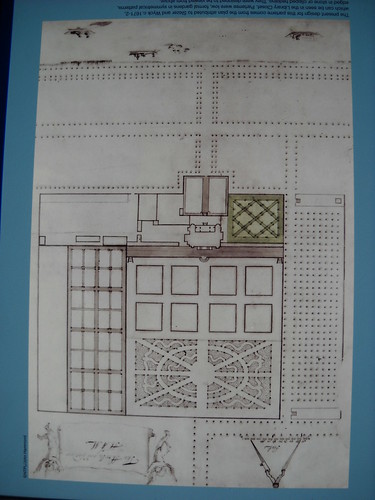

Bird's-eye view engravings of houses and gardens were en vogue and Ham was no exception. When compared to a slightly later plan of the garden by Smythson and Wyck, you can see that little change was made to the garden from its mid-seventeenth century design.

It is the lower plan that was used to guide the restoration, with only a few inauthentic deviations: there's a nifty hornbeam tunnel and yew hedges surrounding the Cherry Garden. Though wonderful and attractive, they aren't historically authentic as the garden would likely have been enclosed by a wall (and if it was, chances are there were espaliered trees on them, possibly of the genus Prunus, hence the garden's name), which now stands only on one side of the garden.

|

The kitchen garden, on the west side of the property, provides a pleasing and productive foreground to the orangery, said to be the oldest in England.

The orangery was an idea imported from Holland, which came over with William and Mary, and the celebrated orangery at Kensington Palace was built by Mary's heir Queen Anne in 1705. The orangery at Ham is believed to be from about 1674, and since both Elizabeth and her husband travelled often to the Continent, they would have been exposed to the latest ideas in home and garden fashion, undoubtedly bringing collections for both back to their home in Surrey.

The orangery now houses a cafe which is supplied with the fresh fruit and veg grown just outside the door. Incidentally, the garden is only planted with historically authentic heritage (or heirloom for my North American friends) varieties. The kitchen garden used to be twice as big as it is now, but the southern half has been converted to a service yard and nursery for the estate.

A day out to see Ham House is definitely a Good Idea, and since it's so easy to reach by public transport, the trip makes for an equally pleasant journey on a fine day. As an example of an intact seventeenth century courtier's home and garden, it can't be beat.

How to get there using London's exceptional public transport:

From London's Waterloo Station take the Southeastern service toward Reading and alight at Richmond Station. Upon exiting the station, go to the bus stop straight ahead and take the 65 or 371 bus via Ham. Alight at The Fox and Duck pub and take the public footpath through the old gatehouse next to the German School. You will soon walk right into the garden wall at Ham.

If you miss the stop, fear not. You can alight at Ham Street and follow the signs, but the walk is longer and not nearly as pleasant as the public footpath.

No comments:

Post a Comment