Way back in the 16th century Tyburn was a wee village out in the country, around the present site of Marble Arch, which took its name from the stream flowing near this spot. Stream? What stream? It's still there, but has been redirected underground. The course of it goes from South Hampstead through St. James's Park and meets up with the Thames at Pimlico near Vauxhall. I was amazed to learn just how many such tributaries have been covered over but if you know how to read the land, you can find evidence of their existence without resorting to trespasses in the sewer system (and who would want to do that anyway? Ick.).

|

| Map of Tyburn Gallows and immediate surroundings, detail of John Rocque's map of London, Westminster and Southwark (1746) |

For reasons unknown (to me), this area became synonymous with capital punishment. Convicted traitors, thieves, murderers, notorious highwaymen, and religious martyrs met their demise here by the tens of thousands over about 800 years, probably more. There is even a convent nearby where the nuns still pray daily for the souls of those who swung from Tyburn Tree. I also like the other notation on the map: "Where Soldiers are Shot". Obviously Tyburn was a sinister place. Somehow I think the soldiers got the better bargain.

But what about this tree? Many who see the plaque might assume it was an actual tree of some historic importance, like Elizabeth's Oak at Greenwich Park. Close, but no cigar. Being before the Industrial Revolution, the tree which made Tyburn famous was indeed made of wood, probably elm, but it's leaves were never green and it's pendulous fruit was eaten by crows, hawks, owls, and other animals with a taste for carrion.

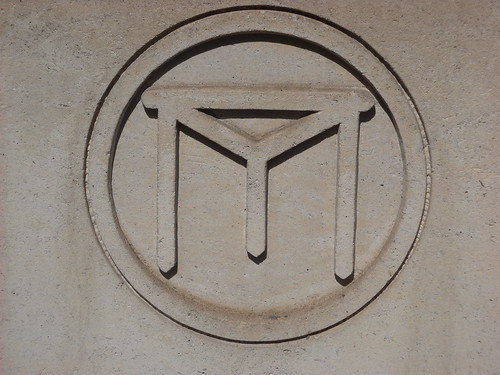

Tyburn Tree, you see, was a gallows. The design wasn't your typical hangman's gibbet of an upright post with an arm, this one was a novel form - a horizontal triangle supported by three eighteen-foot tall legs - which is what made it unique. It was called the "triple tree" and could accommodate mass executions like the one in June, 1649 when 23 men and one woman were hanged together. Other names became attached to the gallows - "The Elms" (presumably the species used to make the structure, elms were widely used in England as ornamental trees and for building), the "Deadly Never Green Tyburne Tree", etc. but if you were a Londoner in the seventeenth century, "the Tree" was sufficient to convey all the information you needed.

My intrepid heroine Celia Fiennes mentions the spot in her essay on London's justice system:

"The manner of Criminalls punishment after Condemnation, wch if it be for fellony or treason their Condemnation of the first is to be hanged, and they are drawn in a Cart from their prisons where they had been Confined all the tyme after they were taken, I say they are drawn in a Cart with their Coffin tyed to them and halters about their necks, there is alsoe a Divine with them that is allwayes appointed to be with them in the prison to prepare them for their death by makeing them sencible of their Crimes and all their sins, and to Confess and repent of them. These do accompany them to the place of Execution wch is generally through the Citty to a place appoynted for it Called Tiburn. there after they have prayed and spoken to the people the minister does Exhort them to repent and to forgive all the world, the Executioner then - desires him to pardon him and so the halter is put on and he is Cast off, being hung on a Gibbet till dead, then Cut down and buried unless it be for murder; then usually his body is hung v up in Chaines at a Cross high road in view of all, to deterre others."

It was conspicuously positioned smack in the middle of the road where the present day Oxford Street and Edgware Road meet. It's even marked on this map of Queen Anne's London circa 1702:

These roads follow the routes of the Roman roads from London and were, at the time, one of the main routes in and out of the city. Every one passing by would get a very clear picture of the fate that awaited them should they decide not to obey the law of the land. Hangings were a public spectacle, usually held on Mondays, drawing crowds of thousands from miles around. The prisoners were conveyed to the Tree by horse-drawn cart from the prison at Newgate and later the gaol at Southwark. The enterprising citizens of Tyburn would erect stands for the spectators to watch the unfortunate 'dance the Tyburn jig' (Take another look at the Rocque map. See the dark curved shape hugging the street corner? Spectator stands. I'd bet my lif...er, my pruning knife on it).

Samuel Pepys mentions these spectacles in his diary, noting on 19 April 1662 seeing three criminals being conveyed to 'Tiburne' and again on 23 October 1668, "and so away with Mr. Pierce, the surgeon, towards Tyburne, to see the people executed; but come too late, it being done; two men and a woman hanged, and so back again and to my coachmaker’s..."

Among the more notable executions was the body of Oliver Cromwell, along with those of Henry Ireton, John Bradshaw, and Thomas Pride, which were exhumed and hanged posthumously on 30 January 1661, symbolically the 12th anniversary of the beheading of Charles I. Pepys wrote of his wife and Lady Batten going to watch the spectacle. The bodies were then buried beneath the gallows.

|

| wiki |

Some interesting trivia that is associated with this type of execution: the criminals were transported by cart, or wagon, to the execution site but were allowed to make at least one stop on the way for a jug of ale. After downing this, their last draught, they were compelled to get back 'on the wagon', never to taste alcohol again.

The ingenious new design for the gallows was apparently the brain child of a man called Derrick. Mr. Derrick was a hangman at Tyburn, a position he may have gladly accepted in lieu of hanging there himself for his crimes. He's credited with devising the new system of ropes and pulley used on the Tree, features still used in other machines now commonly known as 'derricks' - as in an oil derrick. In an ironic twist, Derrick was the hangman at the execution of the man who had granted him his so-called freedom several years before.

It's one of those macabre and somber aspects of history that I find eerily fascinating but it seems that most people haven't a clue now what that plaque in the ground in meant to represent. One blogger I came across suggested erecting a copy of the Tyburn Tree on the spot. Just imagine what that would do to the landscape. It would certainly be an effective measure for traffic calming.

These days the only spectacle people flock to see is the latest film at the Odeon (which stands where Tyburn House used to) or the latest protesters at Speaker's Corner and the nuns of the convent down the block still pray for the martyrs who lost their lives here. It's one of those events in history we just can't imagine. Hollywood tried, and there's a movie clip on YouTube that gives an idea what it might have been like, though I doubt very much that many made such a daring escape (I didn't post the video here because parts of it are kind of graphic and this is, after all, a family-friendly blog).

So next time you're in London up by the Marble Arch, wander over to the flat concrete of the traffic island and look around. Then try to imagine standing in the chilling shadow of the Tyburn Tree.

No comments:

Post a Comment